UAE Briefing Mission

As part of the Rethinking Yemen’s Economy initiative, the Development Champions and

Development Champions Forums (DCF) initiative aims to contribute to and support the advancement towards inclusive and sustainable development and peace

The Development Champions are a group of Yemeni experts with broad expertise and knowledge in economic and social development.

As part of the “Rethinking Yemen’s Economy” initiative, the Development Champions Forum met in Amman, Jordan, between April 29 and May 1, 2017, to discuss practical interventions necessary to address the multiple and varied economic challenges facing Yemen. These challenges were identified within three main, if overlapping, categories; the food security crisis, the problems faced by the banking industry, and the collapse of basic service delivery.

In regards to the food crisis, the Development Champions’ recommendations called on the international community to move quickly in fulfilling all aid pledges. The champions also emphasized that aid should be cash-based rather than in-kind assistance whenever possible. They called on all parties to the conflict to work towards removing the logistical and financial obstacles affecting the importation and distribution of food and medical supplies, and to urgently improve the management of major commercial entry points, such as the ports of Hudaydah and Aden.

Regarding the banking sector, the Development Champions’ called on all parties to work towards a united and functioning Central Bank of Yemen (CBY), and stressed on depositing all public revenues in CBY accounts. The champions recommended that international aid funds should be directed to support Yemen’s foreign exchange holdings, in order to facilitate food and medicine imports.

Regarding public service delivery, the champions recommended to focus support on empowering local authorities and building their capacity in service delivery, as well as engaging the Yemeni diaspora in supporting critical service sectors and encouraging international and local NGOs to provide keys services where required.

Introduction:

Over the past six years Yemen has been experiencing a period of widespread destabilization, which intensified in September 2014 and resulted in full-blown civil war and international military intervention in early 2015. While the violence has been vicious and destructive, by far the most damaging consequences for the wider Yemeni population have been how the conflict has undermined the systems by which the country functions – devastating the economy, social integration, the humanitarian situation and developmental progress. The result is that millions of people in Yemen are now enduring severe economic deprivation and near-starvation.

In an effort to identify practical and realistic interventions to address the most critical challenges currently facing Yemen, a diverse array of Yemeni social and economic development experts from the public, private, and academic fields gathered for the first Development Champions Forum in Amman, Jordan from April 29 until May 1, 2017. The Forum was part of the “Rethinking Yemen’s Economy” initiative, which aims to identify the country’s economic, humanitarian, social and developmental priorities in light of the ongoing conflict in Yemen, and to prepare for the post-conflict recovery period. The recommendations from the Forum are intended to guide the policy interventions of the international community, regional powers, the Yemeni government and all relevant stakeholders in Yemen.

This brief outlines the priorities identified by participants of the Development Champions Forum as the most critical issues facing Yemen today, and their recommendations for addressing these priorities in the short term. It should be noted, however, that participants widely acknowledged that the underlying cause of the immense suffering facing Yemenis is the ongoing war, and without an end to the war all of the following recommendations will be limited in effect and ultimately unsustainable.

The Food Crisis

Background

Prior to the current crisis Yemen was already the poorest country in the Middle East and North Africa and highly food insecure, with imports accounting for almost 90% of the country’s staple foods. The ongoing conflict has severely curtailed commercial imports and humanitarian aid deliveries from reaching Yemen, while violence within the country and widespread fuel shortages have disrupted internal food distribution networks. These obstacles to food delivery have decreased food availability and dramatically increased food costs, while the conflict has simultaneously devastated per capita purchasing power through the almost complete suspension of normal economic activity, and the consequent increased unemployment and loss of income.

The cumulative result is that in February 2017 the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) declared Yemen the “largest food security emergency in the world”; as of May 2017, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) stated that 17 million people in Yemen required food assistance, with 7 million of these facing a “food security emergency” – this is the Phase 4 classification on the UN’s Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) index and the last step before the declaration of famine and humanitarian catastrophe. There are 2.2 million children suffering severe acute malnourishment, with one child dying every ten minutes of preventable causes. Almost every governorate along Yemen’s western and southern coast is suffering a food security emergency.

Despite the High-Level Pledging Event for the Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen in Geneva in April – during which various countries and organizations made pledges amounting to $1.1 billion – as of May 9, 2017, donors had delivered funds amounting to only 18.3% of the United Nation’s $2.1 billion humanitarian appeal for Yemen for 2017.

In light of these circumstances, the Development Champions recommend the following:

Challenges Facing the Banking Sector

Background

Security and political instability in Yemen since the early 2000s, the country’s association with terrorism and arms smuggling, as well as weak governance and judicial structures, made Yemen a “high-risk” country for the global financial system. Shortly after 2010, American banks then began closing the accounts of Yemeni banks in the United States, which increased the burden and costs foreign banks sustained when dealing with Yemeni banks. With the start of the current conflict and Yemen coming under UN Chapter 7 jurisdiction, large European and American banks ceased to interact with Yemeni banks completely, compounding the burden and costs of international transfers to and from Yemen.

Yemeni banks were then prohibited from sending physical cash to foreign correspondent banks, leading to a large decline in the accounts of Yemeni banks at these foreign correspondent banks. Yemeni commercial banks became unable to meet the needs of Yemeni importers, in turn driving importers to the black market and money exchangers to buy and sell currency and make international payments, drawing liquidity out of the Yemeni banking sector. Yemeni banks became both unable to honor customer requests to withdraw cash – leading to further hoarding outside the banking system – and had no domestic currency to deposit at the Central Bank of Yemen. These multiple, interrelated and mutually reinforcing factors helped instigate a severe public sector cash liquidity crisis in mid-2016.

A further central challenge facing Yemen’s banking sector is the deterioration of the Central Bank of Yemen’s (CBY) ability to steward the economy. As a result of the armed conflict the Yemeni government lost the vast majority of its revenue resources – such as oil exports, which had been the government’s main source of foreign currency – leading to the depletion of foreign reserves through two years of war. Following the relocation of the CBY headquarters from Sana’a to Aden in September 2016, the CBY also lost the capacity to perform most central bank functions.

In light of these circumstances, the Development Champions recommend the following:

The Collapse of Basic Public Services

Background

Basic public service delivery in Yemen has long been inconsistent and focused on urban areas; for instance, even before the current conflict almost none of rural Yemen was connected to the national electricity grid. Since the beginning of the current crisis, however, two factors in particular have led to an almost complete erosion of most public services. First, the steep loss in public revenues: Oil exports – previously two-thirds of government revenue – have been stopped completely due to the conflict, with tax and tariff revenue also plummeting amidst general economic collapse; in response, the government authorities cut all non-essential spending in 2015 and focused expenditures on continuing to provide public sector salaries only. Second, the discontinuation of public sector salaries in September 2016 due to a severe public sector cash liquidity crisis (mentioned above): as of May 2017, the vast majority of Yemen’s 1.2 million public servants have not received their salaries for seven months.

Public service delivery has thus been decimated, helping to undermine many of the systems Yemenis depend upon. For instance: garbage has piled in the streets uncollected and waste management systems have broken down in many cities, helping to create a rapidly spreading cholera outbreak; roughly half of Yemen’s public healthcare facilities are no longer operational, and major shortages in staff and medicine have left those still open only partially functioning; the UN has also reported that some 4.5 million school children may not finish the school year because of the disruption in public education.

In light of these circumstances, the Development Champions recommend the following:

As part of the “Rethinking Yemen’s Economy” initiative, more than 20 of the leading socioeconomic experts on Yemen converged for the second Development Champions Forum on January 14-16 in Amman, Jordan. Among the urgent topics of discussion was the deterioration of the value of the Yemeni rial (YR), the magnifying impact this is having on the humanitarian crisis, and the need to re-empower the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) as the steward of the rial and the economy generally. This policy brief is an outcome of those discussions, and the recommendations it includes collectively underline the need for the CBY to function in a more coherent, assertive manner – whereby its various branches operate as a united entity that is able to draft and implement monetary policies for Yemen as a whole. This paper includes further input from the Development Champions following the announcement by Saudi Arabia on January 17 of a $2 billion deposit to the CBY.

The primary reason Yemen is experiencing the world’s largest food security emergency is that millions of people cannot afford to buy the food available in the local market. The ongoing conflict has spurred myriad factors contributing to this crisis, such as general economic collapse and widespread loss of livelihood, restricted naval and air access to the country and internal transportation challenges that are inflating costs for importers. Imports and international trade have also been stifled financially: Yemeni commercial banks have been facing difficulties in transferring foreign currency banknotes abroad due to the air restrictions on Sana’a airport, while American and most European banks have closed the accounts Yemeni commercial banks held abroad due to compliance concerns regarding obligations to international money laundering and counter-terrorism financing standards.

In addition to these factors, the depreciation of the rial has severely impacted purchasing power in Yemen. Prior to the current conflict, the exchange rate was at YR 215 to US$1. By mid January 2018, the rial was trading at YR 530 to US$1 (before the $2 billion Saudi deposit was announced). For in-depth analysis on the the depreciation of the YR and the major contributing factors, see the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies’ (SCSS) October economic bulletin: Renewed rapid currency depreciation and diverging monetary policy between Sana’a and Aden.

[1] For details please see: CBY, “Law No. 14 of 2000 on the Central Bank of Yemen”, available at: http://www.centralbank.gov.ye/App_Upload/law14.pdf (accessed February 3, 2018).

The current humanitarian crisis in Yemen has been precipitated by almost three years of civil war and regional military intervention, with the United Nations declaring the country the world’s largest humanitarian emergency in January 2017. At the end of last year the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) released its 2018 Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) in which it reported that roughly 22.2 million Yemenis were in need of some kind of humanitarian protection or assistance, of which 11.3 million were in acute need. This included 17.8 million Yemenis who were food insecure, of which 8.4 million were severely food insecure and at risk of starvation. Some 16 million people were without access to safe water and sanitation; 16.4 million had limited or no access to healthcare, with almost half of the country’s hospitals and clinics essentially out of operation. Both the lack of clean water and limited health care have in turn helped catapult the number of suspected cholera cases in Yemen to more than 1 million. As of December 2017, more than 1,800 schools were damaged or destroyed, which, compounded by three quarters of public school teachers going unpaid for more than a year, had left roughly 2 million children out of school.

The humanitarian crisis in Yemen is immense and complex, involving a vast array of interrelated and overlapping factors. What is clear, however, is that while international humanitarian actors have been dramatically scaling up operations to address this crisis since 2015, it is overwhelmingly the Yemeni private sector that has stopped the dire situation from being unfathomably worse. Yemeni business owners – in facilitating everything from imports, to transportation logistics and cash aid distributions – have prevented the country from sliding into mass famine. Private sector businesses have similarly offered a measure of relief from state collapse, which has been precipitated by the evaporation of government revenues and suspension of most public sector operating expenditures, such as salaries for most of Yemen’s 1.2 million civil servants.

Private Sector Role in Mitigating the Humanitarian Crisis

Yemen has historically depended on imports to meet as much as 90 percent of the population’s food needs. According to the UN’s Logistics Cluster, between January and March 2017 commercial importers accounted for 96.5 percent of the more than 1.3 million metric tons (mt) of food entering the country; humanitarian actors accounted for the remaining 3.5 percent. With regard to fuel over the same period, commercial importers accounted for almost all of the 526,000 mt arriving to Yemen. As OCHA states in the 2018 HNO: “Just as humanitarian assistance cannot compensate for public institutions, it also cannot replace commercial imports and functioning local markets to meet the vast majority of Yemenis’ survival needs.”

The erosion of government services has seen, among other things, public sector electricity production essentially fall to zero across most of the country. In response, commercial businesses have facilitated the rapid widespread adoption of solar power for households in many areas, while also providing access to industrial generators, equipment, parts and expertise to maintain the functionality of various water systems and health care facilities in major Yemeni cities, notably Sana’a, Hudaydah and Taiz. Many private medical facilities have also remained open — often offering free services to those unable to pay — in areas where public clinics have closed, while Yemeni businesses have also facilitated the flow of medical supplies to pharmacies and public, private and humanitarian facilities around the country.

An August 2017 United Nations Development Program survey of 53 small, medium and large private sector organizations in Yemen, across all industrial sectors, found that four out of five were assisting conflict-affected persons in the country. These organizations reported that the largest forms of assistance they provided were financial, food and health services.

This author’s own survey of Yemeni business owners in November 2017 found that all respondents saw themselves as engaged in trying to mitigate the humanitarian crisis.[1] These actions ranged from cash distributions, to food basket preparation and distribution, to supplying medical equipment for the cholera campaign. Despite the limited market demand for their commodities, all business owners interviewed said that they had kept the majority of their workforce – though through negative coping strategies, such as decreasing salaries and benefits, as well as reducing working hours – and that they considered sustaining these workers as part of their overall efforts toward mitigating the crisis.

The majority of the business owners believed and were involved in corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities as part of their contribution to humanitarian action; one reported having a charitable foundation, while the rest distributed support through their companies. Regarding the latter, for aid distribution purposes the companies had developed and maintained databases of beneficiaries using informal networks of families, friends and neighborhood connections. Typically, company staff with experience in humanitarian relief delivered the support. The business owners said these CSR activities predated the current conflict, though, since the current conflict began, the level of CSR activities they engage in has fallen somewhat.

Relations with International Humanitarian Actors

Private businesses have also played an essential role in the distribution of international humanitarian aid in Yemen, including both cash transfers and physical goods. For instance, through 2017 one Yemeni microfinance bank recorded some 1.5 million cash transfers worth approximately 29.5 billion Yemeni rials to humanitarian aid recipients across Yemen.[2] In another example, in 2015 humanitarian agencies had 63 trucks carrying relief supplies, including food baskets and medicine, stranded in Sana’a due to the fighting. Private sector business networks intervened, facilitating negotiations between belligerent parties on the ground, resulting in the trucks being released and the aid reaching four besieged districts in Taiz and another four in Aden.[3]

Author interviews with Yemeni business owners and a number of international humanitarian agencies’ staff indicated that humanitarian actors rely on the private sector to provide supply chain services such as transportations, warehousing, and clearing and forwarding services.[4] April through September 2017, most humanitarian actors active in the cholera response effort also relied on Yemeni businesses to source needed medical supplies.[5] This was due to the urgency of the crisis and international humanitarian actors’ inability to quickly procure the needed supplies from outside Yemen.

Business owners surveyed for this paper said that they are providing UN agencies, international and local nongovernment organizations with various goods and services, such as vehicles, generators, spare parts and maintenance, food baskets and blankets, and distribution services. In one instance, a business owner described how he had helped establish and was continuing to coordinate a working relationship between an INGO and a local NGO. A further example is that of another business owner, who operates a medical insurance company and who used his in-country networks to help Marie Stopes International be able to support 1,000 medical patients in Sana’a, suffering from ailments such as diabetes, high blood pressure and chronic kidney problems, through the local NGO Hamunat al-Yemen. Through the system they developed, Hamunat al-Yemen would identify beneficiaries amongst disadvantaged populations and, based on the medical insurance company’s advise, direct them to pharmacies to receive medicine paid for by Marie Stopes International. As of this writing, the three parties were planning to launch a new phase of the project to target more poor patients.

In regards to the procurement process, surveyed business owners generally stated that they won their contracts with international humanitarian actors through a tendering processes; one stated, however, that he provided commodities for INGOs through his “personal network.”

The Need for Better Coordination

Surveyed business owners identified several difficulties in dealing with international humanitarian actors, notably in regard to communication with UN agencies and INGOs. These difficulties primarily concerned the tendering process and follow-through; common complaints were that points of contact with INGOs were often unclear, as were INGO standards and requirements. Consultation with the private sector regarding the targeted communities was also often lacking, meaning much of the value-added expertise and capacities of the private sector were going underutilized.

Business owners also described a process in which some INGOs limited their outreach to pre-selected suppliers and rarely offered new businesses the opportunity to bid on tenders. Transparency in the INGO process of vendor selection was thus identified as an area requiring improvement to ensure strong trust and better coordination between INGOs and the private sector. The business owners also noted that the procurement policies of UN agencies and INGOs at times oblige or encourage direct procurement from outside Yemen.

The business owners generally agreed that there needed to be a coordination mechanism established between the private sector and humanitarian actors that would help encourage local procurement and harness the opportunities for a mutually beneficial relationship. The UNDP survey from August 2017 indicated that there was some confusion regarding whether such a coordination mechanism exists: 57 percent of business owners answered “no” to the question: “Is there a coordination platform dedicated to private sector’s humanitarian assistance and recovery efforts in Yemen?” However, all respondents of the UNDP survey said they believed that such a coordination mechanism was necessary, with almost all saying they would participate in the platform if it did exist.

Operating in a Devastated Economy

Even before the current conflict erupted, Yemen was among the poorest and least developed countries in the Middle East and North Africa; since the conflict began the situation has deteriorated substantially. Yemen’s Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation reported that Yemen’s gross domestic product declined 14.4 percent in 2017 which, following contractions of 15.3 percent in 2016 and 17.6 percent in 2015, equals a cumulative economic contraction of 40.5 percent since the beginning of 2015. As a result of this economic collapse private sector operations have sustained significant losses. Commercial businesses have on average cut operating hours by half, with layoffs estimated at 55 percent of the workforce. This shift has been spurred by surging costs, due to insecurity and shortages of inputs, and falling demand for goods and services, with public purchasing power tumbling on the back of widespread livelihood loss and domestic currency depreciation.[6] A general shortage of foreign currency in Yemen and liquidity challenges related to the domestic currency have also presented importers with increased challenges and costs.[7]

Since the Saudi-led military coalition began to intervene in the Yemen conflict in March 2015, it has imposed severe restrictions on imports entering Yemen. Business owners surveyed by this author said these restrictions have had a crippling impact, leading to a significant increase in shipping and insurance costs for imports. Among other significant challenges they noted were: increased customs tariffs after goods are offloaded, the long procedures for releasing shipments, the unsafe road transportation networks in Yemen, and the difficulty in making money transfers with foreign business partners.

On November 6, 2017, the Saudi-led coalition escalated the import restrictions to a complete closure of all ports, with the immediate impact in Yemen being huge price surges for almost all basic commodities and shortages of many, particularly fuel. Over the subsequent month, the coalition eased restrictions somewhat, allowing imports to resume normally in areas of Yemen’s south held by forces affiliated with the internationally recognized Yemeni government, and later allowing limited UN deliveries to Hudaydah seaport and Sana’a airport, both in Yemen’s north and held by Houthi forces. The Saudi-led coalition announced on December 20 that it was allowing Hudaydah port to reopen to commercia.

Looking Ahead

The number of private Yemeni enterprises engaged in business relations with international humanitarian actors has increased over time, with the scaled up aid efforts becoming new business opportunities in the country and creating a competitive market.[8] There is, however, vast untapped opportunities for both parties in creating better cooperation and coordination mechanisms.

The private sector actors – especially businesses involved in importation, distribution, retail and transportation, in addition to the business conglomerates – have a great deal of potential value-added to offer international humanitarian actors in informing the design and implementation of humanitarian support, which would significantly boost the impact of the humanitarian crisis response in Yemen. Yemeni businesses could increase the efficiency and reach of foreign aid funds by allowing humanitarian actors to capitalize on the private sector’s business networks across the country, their ability to adapt to changing dynamics within local communities, and their ability to navigate between the belligerent parties.

Additionally, the business humanitarian actors are currently bringing the Yemeni private sector is helping many companies stay operational, maintain current employees, and at times create new employment opportunities. Humanitarian actors channeling more of their business through the Yemeni private sector and pursuing local procurement would further help local companies maintain current employees and create new jobs, thereby boosting local employment, local purchasing power and stimulating a positive cycle of market demand. More foreign aid funds spent in Yemen would also provide much-needed foreign currency to the local market, which in turn would help stabilize the domestic currency.

A leading UN agency in Yemen supported such increased cooperation and coordination between international humanitarian actors and the Yemeni private sector. In response to this author’s queries, a World Food Program logistics official stated that:

Considering the vital role that private businesses play in the country and their resilience, humanitarian actors can help to facilitate the private sector importation of commodities and supplies by considering them in the humanitarian procurement process from outside the country. A private sector lead will support the effort to avoid local economy collapse and the further deterioration of the humanitarian situation in the country.

Recommendations

Notes:

[1] This author distributed a qualitative survey and received responses between November 22-29, 2017, while also conducting several in-person follow-up interviews between January 1-4, 2017. Five of the seven respondents owned networks of large companies – defined as having more than 50 employees and overseas branches – involved in various economic sectors including financial services, manufacturing, fast-moving consumer goods, transportation logistics, and education. One survey respondent owned a medium-sized company – defined as having between 10 and 50 employees with branches across the country – operating in the area of ‘power solutions,’ selling and servicing generators and renewable energy equipment. The last of the six survey respondents owned a small company, with between four and nine employees, based in Sana’a and with distribution channels in other Yemeni cities, operating in the field of healthcare and pharmaceutical products. In general the business owners were asked about their understanding of the current humanitarian crisis, their role during the crisis, their relationship with humanitarian actors and their suggestions regarding that relationship.

[2] Author interview with al-Amal Bank Operations Manager, January 4, 2018. Importantly, microfinance industry proponents in Yemen say that humanitarian actors’ engagement of microfinance institutions in the aid response — while crucial to address the immediate survival needs of the population — also poses an unintended challenge to the industry’s future survival. While the majority of microfinance clients — micro-entrepreneurs — and their surrounding communities are in need of the support humanitarian aid programs are channeling through the microfinance banks, industry members say this ‘free money’ is transforming the role these institutions play and the necessary culture they have built in the industry over several decades. The industry players have essentially left their core business model of providing microfinance products — for which customer repayment is required — to being agents of social cash transfer services, without there being a clear differentiation between the two for clients. Microfinanciers say this will impact the recovery of microfinance industry in the long run, particularly when humanitarian actors cease making transfers through microfinance institutions.

[3] Author interview with World Food Program Logistics Officer, December 31, 2017.

[4] Author interview with World Food Program Logistics Officer, December 31, 2017.

[5] Author interview with Dr. Adel Al-Emad, Chairman of Medical Insurance Specialist Company and Mr. Ali Jubari, Advisor to the Federation of Chambers of Commerce, December 2017.

[6] For details, please see: Ala Qasem and Brett Scott, Navigating Yemen’s Wartime Food Pipeline, Deeproot Consulting, November 29, 2017, http://www.deeproot.consulting/single-post/2017/11/29/Navigating-Yemen%E2%80%99s-Wartime-Food-Pipeline; Amal Nasser and Alex J. Harper, Rapid currency depreciation and the decimation of Yemeni purchasing power, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, March 31, 2017, http://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/89

[7] For details, please see: Mansour Rageh, Amal Nasser and Farea Al-Muslimi, Yemen Without a Functioning Central Bank: The Loss of Basic Economic Stabilization and Accelerating Famine, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 2, 2016, http://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/55

[8] Author interview with World Food Program logistics official, December 31, 2017.

* This policy brief was prepared by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, in coordination with the project partners DeepRoot Consulting and CARPO – Center for Applied Research in Partnership with the Orient.

* Note: This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union and the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to Yemen. The recommendations expressed within this document are the personal opinions of the Development Champions Forum participants only, and do not represent the views of the Sanaa Center for Strategic Studies, DeepRoot Consulting, CARPO, or any other persons or organizations with whom the participants may be otherwise affiliated. The contents of this document can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union or the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to Yemen.

The second Development Champions Forum of the “Rethinking Yemen’s Economy” initiative recently brought together more than 20 of the leading socio-economic experts on Yemen to discuss the most critical challenges facing the country. Among the key topics included were the need to increase the coverage and efficiency of the campaign international humanitarian organizations and United Nations agencies are undertaking to address Yemen’s humanitarian crisis. Among the major issues the Development Champions identified during discussions were:

The Development Champions also proposed various policy recommendations for international humanitarian actors, the Government of Yemen, the de facto authorities in various parts of the country, as well as Saudi-led military coalition member states and the international community; these recommendations are discussed below.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs reported in the 2018 Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) for Yemen that 22.2 million people – 80 percent of the population – were in need of humanitarian assistance or protection at the end of 2017, of which 11.3 million were in acute need. This included 17.8 million people who were food insecure, of which 8.4 million were “at risk of starvation.”

The humanitarian response efforts last year included eight UN agencies, 36 international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and 147 national non-governmental organizations. The challenges facing these humanitarian actors have been profound, primary among them being the immensity of the crisis. Yemen is currently experiencing the largest humanitarian emergency in the world, the scale and scope of which are severely challenging humanitarian actors’ capacity to assist all those in need, as are the range of needs and the geographic area across which they are spread.

In addition to this, humanitarian actors’ abilities to operate in Yemen and access those in need face severe constraints. Among the many challenges humanitarian actors regularly cite are:

All of these factors have also heavily impacted humanitarian actors’ ability to conduct needs assessments, monitor outcomes and gather other data critical to implementing timely evidence-based programming. The warring parties’ sensitivities to such data collection, in particular in Houthi-controlled areas, has also often led them to actively block such activities.

While the Humanitarian Country Teams (HCTs), Clusters, and Inter-Cluster Coordination (ICC) between the international humanitarian actors are well established and functioning, there is limited coordination with the Yemeni private sector and with other local actors. This creates an inherent gap between the demand and supply of aid supplies within the country. It misses the opportunity for the humanitarian actors to address their current inability to stock food and supplies at sites around the country and potentially increases costs of delivery as the humanitarian actors try to build their network and infrastructure for delivering aid to locations where they did not operate previously.

Previous reconstruction efforts in Yemen following conflict or natural disaster have suffered from lack of coordination with and unrealistic expectations from international donors, as well as the Yemeni government’s limited capacity for aid absorption and project implementation; as a result, there was little tangible long-term impact.

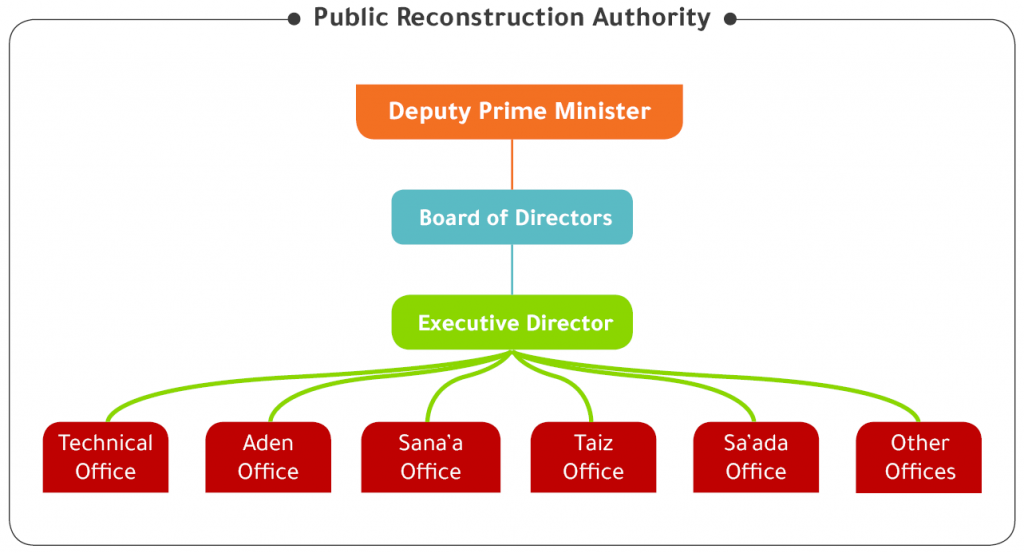

In light of lessons learned from similar post-conflict contexts and Yemen’s own history of reconstruction efforts, this policy brief proposes an institutional structure for a future reconstruction process in Yemen: a permanent, independent, public reconstruction authority that empowers and coordinates the work of local reconstruction offices, established at the local level in areas affected by conflict or natural disasters. This proposal does not arise only from these lessons learned, but also from the immediate need for such an institution to begin planning and implementing reconstruction work to the greatest extent possible.

This reconstruction authority should have a clear mandate to manage all tasks required in reconstruction following the current conflict, but also future crises. Its board of directors should include a range of stakeholders and should be chaired by a deputy prime minister for reconstruction to ensure it has the highest level of support. It should take an inclusive, multi-level, mixed institutional approach, have a clear long-term plan for building state capacity, and establish its own monitoring and evaluation unit to demonstrate a commitment to transparency. Most importantly, it should establish a clear framework for working closely with all stakeholders.

The current conflict in Yemen follows decades of political and economic turmoil. Any future reconstruction efforts will face a daunting task. For example, World Bank estimates from 10 cities in Yemen revealed a quarter of the road network was partially or fully destroyed as of 2016, with power production halved and half of all water, sewage and sanitation infrastructure damaged. With the intensification of the conflict since, it is expected that current levels of destruction are far greater.

In early 2017 the United Nations also declared Yemen the site of the world’s worst humanitarian crisis; as of April 2018, roughly 22.2 million Yemenis were in need of humanitarian assistance, including 8.4 million at risk of starvation. The country’s gross domestic product declined an estimated 47.1 percent from 2015 to 2017, while 40 percent of households have reported the loss of their primary income source. Most public services have been suspended, leaving 16 million people without access to safe water and 16.4 million with limited or no access to healthcare.

There is little sign of the conflict ending soon. Nevertheless, stakeholders concerned with establishing lasting peace in Yemen must urgently begin laying the groundwork for a comprehensive reconstruction framework to implement in the eventual aftermath of fighting. Experience has shown that it is never too early to begin planning for reconstruction.

This policy brief, which is based off of a more extensive White Paper, consists of the following sections:

The policy brief seeks to identify how to ensure the proper flow of funds and the timely completion and overall quality of post-war reconstruction projects. Beyond this, however, it emphasizes the importance of national ownership – meaning the inclusion and buy-in of all Yemeni stakeholders. Such an inclusive framework builds Yemen’s capacity to meet the basic needs and rights of its own people, thereby putting the country on the path toward lasting recovery.

Yemen has had numerous experiences with reconstruction efforts, given its decades-long history of poverty, natural disasters, and conflict. In recent decades, several natural disasters have hit Yemen. The 1982 earthquake in Dhamar killed up to an estimated 2,500 people and injured a further 1,500, with US$2 billion in losses. Although the independent Executive Office for Reconstruction, created following the earthquake, delivered thousands of earthquake-reinforced housing units, most of these remain uninhabited even today, due to their cultural unsuitability. The reconstruction office was also ineffective due to a limited capacity for coordination or monitoring. The 2008 flood in Hadramawt and al-Mahra caused an estimated US$1.6 billion in damage. The Hadramawt and al-Mahra Reconstruction Fund succeeded in engaging local stakeholders. However, it lacked any coordination mechanism or monitoring framework. Despite having resources, it lacked effectiveness: it struggled to utilize the US$210 million it was allocated, spending only 70 percent of its total available funding.

Yemen has also seen years of chronic unrest. Recurring conflict in Sa’ada governorate from 2004-2010 killed hundreds and wounded thousands more, while causing an estimated US$600 million in damages. The Sa’ada Reconstruction Fund had a US$55 million budget allocated from the Yemeni government. The fund neglected public infrastructure at the expense of rebuilding private properties and faced widespread accusations of “reconstruction bias,” directing rebuilding efforts to areas based on personal affiliations rather than need. The occupation of Abyan governorate by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and associated fighting in 2011-2012 left damage estimated at US$580 million. The Abyan Reconstruction Fund was allocated US$46.5 million. It did little to absorb this funding and quickly developed a reputation for mismanagement, corruption, and embezzlement. The fund’s evaluation report estimated US$4.2 million of fraudulent costs and a further US$1.4 million reported as compensation for ‘ghost’ beneficiaries.

At the demand of international donors, and following 2011 protests against then-President Ali Abdullah Saleh, the Yemeni government established the Executive Bureau in 2012 to build state capacity. However, it did not have the political power necessary to overcome resistance from ministries who viewed it as competition. When Houthi fighters seized Sana’a in late 2014, the Executive Bureau’s ability to function was further curtailed. Despite later attempts to revive it, the Bureau’s World Bank funding expired in mid-2015; as the security situation deteriorated, funding for the Bureau was withdrawn.

Yemen also has examples of innovative initiatives for delivering public services, though not in a post-conflict context. Since the mid-1990s, semi-autonomous agencies have operated parallel to the central government to deliver public services in rural areas. The Public Works Project, the Social Welfare Fund, and the Social Fund for Development provide models for effective, efficient, and transparent services provision in Yemen. They have a carefully designed legal mandate that provides sufficient autonomy while having a well-defined relationship with the government. However, they are designed to be only short-term alternatives; there is no clear strategy for how they might be permanently integrated into the government.

As mentioned above, previous Yemeni reconstruction efforts have shown an inability to absorb aid or to implement projects effectively. Past reconstruction initiatives thus do not provide a successful model for future reconstruction, particularly given that the current war’s destructiveness far outstrips that of past disasters or conflicts. However, there is the potential to build on the existing institutional blueprint of the Executive Bureau and, similarly, to initiate reconstruction interventions through local models that already have community buy-in, national reach, and a professional workforce: the Social Fund for Development, the Public Work Projects, and the Social Welfare Fund.

This paper proposes a way forward for reconstruction in Yemen through creating a proactive institutional framework to deal with the aftermath of the current war as well as future crises. This requires the establishment of a permanent independent Public Reconstruction Authority (PRA) operating to empower and coordinate the work of local reconstruction offices, created at the local level in areas affected by the conflict or natural disasters.

The mandate of the authority should be to manage all the tasks required in reconstruction: current and future post-conflict or disaster reconstruction planning; policy design; funding and fundraising; and coordinating with all stakeholders. The mandate should also include the tasks required for a transparent process: monitoring and evaluation; reporting; and overseeing strategic national projects.

To fulfill this mandate, the reconstruction authority should:

To manage relations with stakeholders, the reconstruction authority should:

Reconstruction in Yemen must follow a model that responds to the realities on the ground, builds state capacity, ensures transparency, and coordinates efficiently. It must foster trust not only among donors but among Yemeni political actors and citizens at large. It must coordinate well with international donors while maintaining Yemeni ownership of reconstruction. Focusing efforts not only on affected areas but the Yemeni population as a whole will provide basic services and create job opportunities across regions. People are less likely to return to conflict if they are constructively occupied, earn an income and can plan for the future. They are also more likely to support the peace process if they experience increased well-being, see an improvement in public services, and hear of successful development projects. As such, an institutional model for reconstruction that emphasizes national ownership, transparency, and inclusiveness will have the best chance to consolidate peace in the long term.

The ongoing conflict in Yemen has imposed grievous costs on Yemenis, damaging lives, property and infrastructure and collapsing the country’s already fragile economy. And yet the conflict will eventually subside. Although some reconstruction projects have begun, they have generally been undertaken haphazardly and not as part of a comprehensive and structured plan. Post-conflict reconstruction following the war must address the basic needs and rights of the Yemeni population and put the country on the path toward sustainable peace and development.

This report examines the literature regarding post-conflict reconstruction and draws lessons from the reconstruction experiences of Afghanistan, Iraq, and Lebanon, in addition to multiple past post-crisis reconstruction efforts in Yemen itself. Past Yemeni efforts in the wake of disasters and conflicts have been ad hoc and reactive. The Yemeni government has demonstrated a limited capacity for aid absorption and weak capacity for project implementation. Donors have contributed to these poor results, to a certain extent, by circumventing the state and disbursing aid directly, thereby ensuring that the state do not develop the inherent authority to manage long-term reconstruction. Furthermore, actual donor disbursements often fail to keep pace with initial donor aid commitments.

Drawing on lessons from past reconstruction efforts, this report proposes a new institutional structure for a proactive, permanent future reconstruction authority in Yemen. Because the war has both damaged the central government’s capacity to provide services and worsened regional and sectarian fragmentation, it is impractical to rely solely on the central government for post-conflict reconstruction throughout Yemen. Therefore, Yemen should adopt a multi-level mixed institutional approach to reconstruction that closely coordinates with all stakeholders.

Key recommendations

Local councils are among Yemen’s most important state institutions. Responsible for providing basic public services to millions of Yemenis, local councils represent official governance and the Yemeni state for much of the population. The intensification of the conflict between the internationally recognized government, its regional backers and the Houthi group since March 2015, however, has heavily impacted funding and security for local councils, undermining their ability to provide services effectively in most areas of the country.

In many areas, this absence of effective official governance has created fertile ground for non-state actors to exert their influence. In the areas under Houthi control, Houthi supporters closely monitor local council activity. In the southern coastal city of Aden, local councils are caught among competing armed militias that form part of a broader power struggle between southern secessionists and the internationally recognized Yemeni government.

Despite the challenges they face, local councils remain important instruments for coordinating humanitarian relief efforts and local-level conflict mediation. In the absence of central state authority, a number of effective local, self-governance models have emerged, notably in Marib and Hadramawt governorates. At some stage a new system of governance will need to be drawn up to reflect the new realities on the ground; these models may indicate a way forward. Local councils are among the best-equipped and best-established institutions to support a shift away from the previous centralized model.

The currently reduced capacity of local councils is cause for much concern as the conflict rages on and Yemen’s economic and humanitarian crises deepen. Irrespective of how the conflict progresses, it is imperative that local, regional and international actors seek not merely to keep local governance structures from collapse but to enhance the capacities of local councils in post-conflict scenarios.

Local councils are among Yemen’s most important state institutions. Responsible for providing basic public services to millions of Yemenis, local councils represent official governance and the Yemeni state for much of the population. The intensification of the ongoing conflict between the internationally recognized government and the Houthis since March 2015, however, has heavily impacted funding and security for local councils, undermining their ability to provide services effectively in most areas of the country. The reduced capacity of local councils to function is cause for much concern as the conflict rages on and Yemen’s economic and humanitarian crises deepen.

With an aim to inform stakeholders on options for supporting local councils in the near and long term, this policy brief, which is based on a more extensive White Paper , provides insight into the current challenges that local councils face. The first section provides a view of how local governance throughout Yemen is evolving amid conflict and instability. As the conflict creates a political and security vacuum, non-state actors have stepped in to provide services at the local level. Despite the conflict’s negative impact on their ability to operate, however, local councils have acted to coordinate humanitarian aid and to mediate conflict at the local level. In the north, Marib governorate has pushed for greater local autonomy, and, like Hadramawt in the south, has achieved a degree of success in effective self-governance.

Regardless of how the conflict progresses, stakeholders in Yemeni governance must seek not merely to prevent local governance structures from collapse, but also plan in advance to enhance the capabilities of local councils in post-conflict scenarios. As such, the third section of this brief provides recommendations for local, regional and international actors to support local councils in the short term while building towards a longer-term post-conflict stability.

In many areas of Yemen, as the political and security vacuum has widened, local power brokers, including local authorities, have begun to operate with a greater degree of autonomy. Local actors have become increasingly disconnected from developments occurring elsewhere in the country and are more inclined to pursue their own agendas, at times with the support of their respective regional backers. This has led to a rise in non-state actors exerting their influence in local affairs, including the Houthis and a growing variety of actors in southern Yemen.

As the conflict has unfolded and the state’s already limited ability to provide services and security for its citizens has continued to erode, in many areas civilians’ trust in local councils has fallen. In the absence of effective formal governance non-state actors — often armed groups — with greater resources at their disposal have increasingly exerted influence in local affairs.

In Yemen’s north, with the exception of Marib and al-Jawf, the Houthis have exerted influence at the local level through so-called “Popular Committees”.[1] Although the Houthis have not made any substantial changes to the local governance framework, they have at times redirected funds earmarked for local development projects. They monitor local councils located in areas under their control to ensure local councils distribute revenue and channel external humanitarian aid consistent with the agenda set by the Houthi leadership.

In 2015, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) took control of Mukalla in Hadramawt governorate. AQAP integrated itself among local communities by providing social welfare programmes and supplying Mukalla with food and water despite shortages in other areas.[2] Although AQAP’s presence was not unopposed, the group continued to govern until its withdrawal from Mukalla in April 2016.[3] After AQAP’s withdrawal, local authorities in the city struggled to provide services and now depend on external support from international organizations and the Saudi-led coalition.

In other cases, militias fighting on the same side of the conflict nonetheless act in competition when it comes to local governance. In Taiz governorate, where Houthi-Saleh forces began laying siege to Taiz city in March 2015, the Saudi-led coalition, and particularly the UAE, has assisted the rise of Salafi militias. The UAE’s reluctance to engage with Islah — due to the party’s links with the regional Muslim Brotherhood — meant that it turned to other anti-Houthi groups, such as the militias headed by Salafi military commander Adel Abdu Farea, more commonly known as Abu al-Abbas.[4] The UAE’s support of Abu al-Abbas fuelled animosity between his men and Islah-affiliated militias, which on several occasions has led to the outbreak of clashes between these supposedly pro-government factions as they compete for influence on the ground.[5]

The 2015 Houthi-Saleh takeover of several southern districts was debilitating for local institutions providing public services. After retaking these areas, the Saudi-led coalition — and the UAE in particular — assisted in restoring some services. However, the coalition’s backing of multiple, sometimes competing authorities in different sectors, especially security, generated tension and made effective local governance difficult.[6]

As in Taiz, local councils in Aden have been forced to withstand the pressure of regular infighting among competing armed groups. In the southern port city of Aden and across south Yemen more broadly, the conflict has intensified calls for the establishment of a new, independent southern state. The UAE has supported various political and security actors who advocate for southern independence.[7]

In April 2017, Yemeni President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, objecting to the UAE’s ties to southern secessionists, fired a number of southern leaders from his government. The following week these leaders formed the Southern Transitional Council (STC) and rapidly began establishing a parallel structure for local governance across southern Yemen.[8] As the local clout of southern secession leaders has increased, the standing of the Hadi government has decreased. Critics of the Hadi government claim that public service delivery in Aden is being held up by the government’s economic mismanagement and outright corruption.

The continued competition between secessionist forces and Hadi loyalists is destabilizing for local councils in southern Yemen. Animosity in Aden between local UAE-backed forces and other armed factions loyal to Hadi has repeatedly boiled over, with the most recent of many clashes occurring at the end of January 2018. Clashes between the two groups prevent local councils from operating in a secure environment.[9] Aside from the threat of violence, local councils are vulnerable to interference by armed militias eager to assert themselves at the local level.

At the same time, both sides actively interfere in the work of local council members in order to advance their own agendas. Interviews with local council officials reveal some of the challenges facing their work in Aden:[10]

As the overarching conflict has intensified and spread in the past three years, there has been a breakdown in local security. Local police forces and the branches of the judiciary that once helped to maintain a degree of order at the local level have been unable to provide a secure environment in which local authorities can operate. At the same time, local councils have lost much of their funding: in 2015, the internationally recognized Yemeni government, experiencing a sharp reduction in oil and gas revenues due to the conflict, halved the funds it provides to local councils.[11] The January 2018 budget limited the funds allocated to local authorities to paying salaries and covering only 50 percent of operational expenditures.[12] The deterioration of the Yemeni economy has left most local councils unable to collect utility taxes, permit fees, or zakat revenues.[13] While some local councils receive donations from Yemeni businessmen and institutions, most are left without the funds to provide services. The lack of funds has been particularly marked for local councils located in Houthi-controlled areas, due in part to redirection of funds by the Houthis. [14]

However, despite struggling to provide services, local councils have helped to coordinate the flow of external humanitarian aid during the conflict. In a number of governorates, local council members transmit information to international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) through semi-informal communication channels, assisting with humanitarian needs assessments. They have also helped to prevent the spread of cholera by channelling external support to local health facilities. In some instances, local councils in Yemen have played a role in facilitating conflict resolution at a local scale, coordinating local ceasefires, ensuring safe passage of humanitarian aid across frontlines, or organizing prisoner exchanges between warring parties.[15]

Hadramawt, in eastern Yemen, is the country’s largest governorate and most prolific oil producer.[16] Many in Hadramawt have long been frustrated with the lack of oil revenues reinvested into the governorate. Hadramawt’s desire for greater control over — and an increased share in — its own economic resources was one of the central demands made at the Hadramawt Inclusive Conference (HIC) held in April 2017.[17] Since its establishment, HIC and other members of Hadramawt’s socio-political elite have made the governorate’s participation in any future federal state — or an independent southern state — contingent upon it receiving a larger share than it currently does of the revenues from it own resources. Specifically, the HIC demands that 20 percent of oil revenues extracted from Hadramawt be reinvested back into the governorate.[18] It is highly unlikely that local Hadrami officials would be willing to adhere to the former decentralization mechanism defined by the Local Authority Law (LAL) of 2000, which is the legal framework that formally established local councils as government entities.[19]

The internationally recognized government appears to be taking seriously Hadrami demands for a greater share of resource revenues: it now pays the Hadramawt Tribal Confederation (HTC) and Petro Masila, the local oil company that runs the Masila (Block 14) oil field, for access to the field.[20] It also sends payments of cash or fuel to local authorities and the UAE-backed Hadramawt Elite Forces in the coastal city of Mukalla for access to the oil export facilities located there.[21] These payments help to lessen the burden on local councils.

There is also a substantial network of wealthy Hadrami businessmen living in neighbouring Gulf countries; during the conflict, these businessmen have played a significant role in financially assisting local councils to provide services and implement local development projects.

These various revenue streams have thus allowed the authorities in Hadramawt to continue to operate – and with a degree of local autonomy – insofar as they are able to regularly pay civil servant salaries, invest in local services, and finance the development and maintenance of electricity, water and sewage infrastructure.

Prior to the current conflict, and despite the presence of vital energy resources, Marib lacked infrastructural development due to the central government’s monopolization of oil and gas revenues.[23] The current conflict has, however, led to a change in fortune for Marib. The protection offered by Saudi-led coalition forces, coupled with Marib’s own robust and united security apparatus, has allowed the governorate to enjoy a comparatively high level of security.[24] From this position of relative security, in mid-2017 Marib negotiated a deal with the internationally recognized Yemeni government for the governorate to keep up to 20 percent of revenues from oil extracted in the governorate, over which the central government had previously had a total claim.[25]

The agreement reflects a broader effort by Marib’s local governing authorities to take ownership of its oil, gas, and electricity facilities. Since the agreement, local councils have helped to keep energy facilities functional and to increase capacity through consultations with local stakeholders. They supervise the timely distribution of oil, diesel, and gas derivatives to Marib homes. Unlike many local councils in Yemen, they provide public services and coordinate local development projects.

Since taking control of a larger share of natural resource revenues, Marib’s relative economic boom has led tens of thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) to seek refuge in Marib.[26] Despite this influx, Marib is benefiting from a period of relative stability and sustained economic development. In Marib, civil servants are paid and public services are generally provided. Decision making in the local governance model generally includes consultations with various societal groups, even while the authorities remain intolerant of direct political dissent. The governorate has thus come to represent a unique and reasonably effective decentralized model of local governance in Yemen bolstered by the unity of the population, tight-knit security, and economic resources.

The inability of the central government during the conflict to respond to local needs prompted Hadramawt and Marib, two relatively resource-rich governorates, to exceed the legal mandate bestowed upon them by the 2000 Local Authority Law. In both governorates, there is an emerging model of local governance that other governorates could follow, whereby the local community has been more included in decision-making and managing local affairs than it was prior to the conflict, with this being facilitated by both the development of local resources and support from the central government.

Since their inception, local councils have been a critical governing institution in Yemen. However, the ongoing conflict has severely impacted their ability to provide essential services to their communities at a time when humanitarian and economic crises are worsening. In some areas, non-state actors compete to provide services, thereby undermining the trust of Yemeni citizens in local councils. In other areas, local authorities have evolved fairly successful forms of self-governance in the absence of an effective centralized government.

This policy brief has sought to illuminate the challenges faced by local councils during the ongoing conflict. Local, regional and international actors concerned to establish stable and effective governance in Yemen must actively support local councils to meet these challenges. Some current examples, such as Hadramawt and Marib, may guide the future shape of local governance in Yemen. Local councils should play an important role in any future post-conflict reconstruction process, but bolstering local councils should not wait until the end of the conflict. Given how critical a role local councils have played in governance for nearly two decades, they promise to be valuable partners in rebuilding trust and stability.

Regional and international stakeholders should coordinate efforts to restore the CBY to a fully functioning unified national entity. From the onset of political unrest in 2011 until just before the relocation of CBY headquarters in September 2016, the central bank played a vital role in maintaining local councils’ ability to deliver basic services by continuing to disburse civil servant salaries and helping to cover operational costs. It is currently difficult for local councils in any of Yemen’s 22 governorates — with the exception of Marib, and to a lesser extent Hadramawt — to secure sufficient operational revenues.

The international community should take constructive measures to develop a mechanism between the warring parties for the nationwide collection of state revenues such as taxes and customs. The re-establishment of public services in all areas would provide the incentive for the parties to collaborate in this effort. A state budget that reflects the current situation in Yemen will ensure that greater financial support is provided to local councils.[27] The Social Fund for Development (SFD), a quasi-governmental poverty reduction body, can channel allocated revenues to local authorities and can jointly implement public service projects.

International donors and INGOs should enlist local councils as liaison points with local organizations and private sector actors. This approach will increase the councils’ legitimacy and encourage the local community to unite under formal government structures. It may also create a more decentralized service delivery model, which in turn may extend the reach of reconstruction efforts. Any support filtered through the local councils must include an oversight mechanism to avoid misappropriation of funds.

The internationally recognized government should issue temporary regulatory instructions to devolve more of its powers officially to the governorate and district level by:

International stakeholders should target the implementation of local capacity-building programs that improve the performance of the local judiciary and security services. This may also entail financial support to rebuild and improve their capital infrastructure. This will allow judiciary and security services to operate effectively and maintain legitimacy. While acknowledging local complexities, international stakeholders should discourage parties to the conflict and regional players from intervening in the activities of the local judiciary or creating competing entities that undermine state legitimacy.

INGOs and other actors should support community-driven initiatives constructed in such a way that they reinforce the effectiveness of, rather than circumvent, official local government institutions. Promoting bottom-up, inclusive local governance will help to avoid claims of bias or discrimination while curbing the appeal of non-state actors as alternatives to the state.

A comprehensive and realistic assessment of which individuals and groups are in control at the governorate and district levels, as well as an assessment of these entities’ capacities to provide services, will help domestic policy-makers (with the support of the international community) to develop post-conflict strategies to restore state functions, such as the provision of security and public services.

Notes:

[1] Peter Salisbury, “Yemen: National Chaos, Local Order,” Chatham House, last modified December 20, 2017, accessed May 23, 2018. https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/yemen-national-chaos-local-order.

[2] Thomas Joscelyn, “Arab Coalition Enters AQAP Stronghold in Port City of Mukalla, Yemen,” Long War Journal, last modified April 25, 2016, accessed May 23, 2018. https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2016/04/arab-coalition-enters-aqap-stronghold-in-port-city-of-mukalla-yemen.php; Elisabeth Kendall, “How Can al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula Be Defeated?” Washington Post, last modified May 3, 2016, accessed May 23, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/05/03/how-can-al-qaeda-in-the-arabian-peninsula-be-defeated.

[3] Joscelyn, “Arab Coalition Enters AQAP Stronghold in Port City of Mukalla, Yemen.”

[4] “UAE, Saudi Send Weapons to Taiz Resistance,” Emirates 24/7 News, last modified January 7, 2016, accessed May 23, 2018. http://www.emirates247.com/news/region/uae-saudi-send-weapons-to-taiz-resistance-2015-11-07-1.609560.

[5]“عاجل: استشهاد حمزة المخلافي شقيق قائد المقاومة الشعبية بتعز (صورة [Breaking News: Martyrdom of Hamza al-Mikhlafi, Brother of the Popular Resistance Commander in Taiz], Al Mawqea, last modified April 23, 2016, accessed May 23, 2018. http://almawqea.net/news.php?id=7226#.V9k0FJN96lO; “عاجل.. الشيخ حمود المخلافي يكشف عن تفاصيل مقتل شقيقه بتعز” [Urgent: Sheikh Hamoud al-Mikhlafi Reveals the Details of His Brother’s Death in Taiz],” Ababiil, last modified April 23, 2016, accessed May 23, 2018. http://ababiil.net/yemen-news/82187.html; “قائد كتائب حسم يكشف عن ملابسات استشهاد حمزة المخلافي وتفاصيل المكالمة التي اجراها مع الشيخ حمود سعيد عقب الحادثة. [Commander of Haskat Brigades Reveals the Circumstances of the Martyrdom of Hamza al-Mikhlafi and the Details of the Call He Made with Sheikh Hamoud Said After the Incident],” Yemen 24, last modified April 24, 2016, accessed May 23, 2018. http://yemen-24.com/news27572.html.

[6] Researcher interview, Aden senior local council leader, May 2018.

[7] In Aden, and elsewhere across south Yemen, the UAE has assembled, trained, and continued to back a number of local security forces that operate with varying degrees of independence from the internationally recognized government. These forces include the Security Belt forces in Aden, Lahj, and Abyan governorates; the Hadramawt Elite Forces; the Shabwa Elite Forces; and the more recently formed al-Mahra Elite Forces.

[8] “Al-Zubaidi and the STC Members are in Al-Mukalla City,” Southern Transitional Council, 2017, accessed May 23, 2018. http://en.stcaden.com/news/7959. “Al-Zubaidi Issues a Resolution to Appoint Local Leaderships in Shabwah Governorate,” Southern Transitional Council, 2017, accessed May 23, 2018. http://en.stcaden.com/news/8084.

[9] Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, “Yemen at the UN—January 2018 Review,” last modified February 11, 2018, accessed May 23, 2018. http://sanaacenter.org/publications/yemen-at-the-un/5389#Clashes_in_Aden.

[10] Researcher interview, Aden local council officials, May 2018.

[11] Baron et al., “Essential Role of Local Governance;” Oil production has declined annually since 2001. This has placed Yemen’s economy under increased pressure, despite the 2009 opening of Yemen’s liquified natural gas (LNG) terminal in the Balhaf, Shabwa governorate. In 2014, approximately 70 percent of the national budget came from Yemen’s oil and gas resources. Following the escalation of the conflict in March 2015, oil and gas production in Marib, Shabwa and Hadramawt governorates stopped, subsequently depriving Yemen of its major source of revenue. In 2015, there was a 54 percent year-on-year decrease in state revenues for the annual budget.

[12] Researcher interview with confidential source with close ties to CBY in Aden, June 2018.

[13] Zakat is an “Islamic tax” or financial obligation imposed on all Muslims who meet the necessary wealth criteria.

[14] Researcher interviews conducted with local council directors and members in Houthi-controlled areas, September 2017.

[15] Researcher interview, Ibb, October 2017; researcher interview, Marib, September 2017.

[16] In February 2014 oil from Hadramawt accounted for an estimated 53 percent of total oil production in Yemen. See World Bank, Republic of Yemen: Unlocking Potential for Economic Growth (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2015) accessed May 23, 2018. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/23660.

[17] A total of 160 participants attended the conference, which led to the appointment of 52 members that make up the HIC executive decision-making authority.

[18] Researcher interview with Dr. Abulkader Ba Yazid, Secretary General of Hadramawt Inclusive Conference, Jordan, September 2017.

[19] Researcher interview with Dr. Abulkader Ba Yazid, Jordan, September 2017. The central government in Sana’a issued the Local Councils Law in 2000 as a way to try and address calls for greater regional autonomy, particularly among the Houthis in the north and the Southern Movement. The law stipulated that, while the central government would maintain control of foreign policy and national security – and would retain the ability to veto local action – local councils now had responsibility for running day-to-day affairs. The law effectively made local councils one of the most important public institutions in Yemen. Local councils were to be directly elected and were to have greater decision-making authority over financial resources and the implementation of development programs. Although oil and gas revenues remained in the hands of the ruling authorities in Sana’a, local councils were permitted to collect commercial taxes and to tax residents for the use of state-operated utilities such as water and electricity.

[20] Researcher interview with Yemen expert Peter Salisbury, March 5, 2018.

[21] Researcher interview with Yemen expert Peter Salisbury, March 5, 2018.

[22] Large portions of this sections are based on the following: researcher interviews with local council directors in Marib, November 2017; “Yemen’s Urban–Rural Divide and the Ultra-Localisation of the Civil War,” workshop organized by the London School of Economics Middle East Centre, March 29, 2017, London, UK.

[23] According to Yemen’s national statistics, less than 1 per cent of total government expenditures were allocated to Marib in 2015.

[24] Ben Hubbard, “As Yemen Crumbles, One Town Is an Island of Relative Calm,” New York Times, last modified November 9, 2017, accessed May 23, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/09/world/middleeast/yemen-marib-war-ice-cream.html; Adam Baron, “Not Only a Pawn in Their Game,” European Council on Foreign Relations, last modified November 16, 2017, accessed May 23, 2018. http://www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_not_only_a_pawn_in_their_game.

[25] Despite the agreement between Marib and the internationally recognized government, as of this writing ongoing disputes between the CBY’s Marib and Aden branches has led to the Marib CBY refusing to deposit any rents from the governorate’s gas, oil and gasoline production in accounts at the Aden CBY.

[26] Marib-based journalist Ali Aweidhah, speaking to the researchers in June 2018, estimated that Marib’s population grew from some 240,000 people at the beginning of the conflict to some 2.4 million as of this writing.

[27] Researcher conversation with a source with close ties to the CBY in Aden, June 2018.

Local councils are among Yemen’s most important state institutions. Responsible for providing basic public services to millions of Yemenis, local councils represent official governance and the Yemeni state for vast swathes of the population. The intensification of the conflict since March 2015, however, has undermined the councils’ ability to operate effectively in most areas of the country. The councils depend heavily on central government financing and, to a lesser degree, local sources of revenue such as taxes on basic utilities and telephone usage. As such, Yemen’s precipitous economic collapse, the subsequent decline in government revenues and the incapacitation of the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) have compromised local councils’ ability to operate. The nonpayment of civil servant salaries and Yemenis’ decreased purchasing power contribute to Yemen’s alarming humanitarian crisis while limiting local councils’ ability to extract local sources of revenue.

Generally speaking, a shortage of revenues has left local councils across Yemen unable to operate anywhere near to their full capacity. The most obvious exceptions to this rule can be found in Marib and Hadramawt governorates, which enjoy relative stability and comparatively greater economic resources. These local councils are functioning at a much higher level than their counterparts. Some local councils, such as those in Ibb and Hadramawt governorates, have also received donations from Yemeni businessmen that have helped to continue operations to some extent.

The increased violence and instability since March 2015 have also largely overwhelmed local police and the judiciary — institutions that previously provided a degree of local order. As a result, local councils have been afforded little protection in their operations. As the state’s ability to provide either security or public services has eroded, civilian trust in either local councils or the state itself has fallen. In many areas this absence of effective official governance has created fertile ground for non-state actors to assert their authority, including over local councils. The autonomy and maneuverability of local councils in Houthi-controlled areas is restricted by the Houthis’ adoption and implementation of a centralized mode of governance, in which local-level processes such as the distribution of revenues or humanitarian aid are controlled by the Houthis at the center. In the areas under Houthi control, Houthi supporters closely monitor local council activity.

Although interference in local councils is arguably more consistent in Houthi-controlled areas, local councils also face interference elsewhere. Aden is a prime example: local councils in the southern coastal city are vulnerable to interference from competing armed militias that form part of a broader power struggle between southern secessionists and the internationally recognized Yemeni government.